Reducing the size of government.

Streamlining the bureaucracy.

Returning power to the states.

And Equality of opportunity. These are all principles of the Republican Party. Throughout our history, the Republican Party has consistently demonstrated that our party was founded on equality for all. Republicans fought the battle for equality on behalf of our fellow Americans long before it was popular to do so. The Republican Party, since its inception, has been at the forefront of the fight for individuals’ Constitutional rights.

As the party of the open door, while steadfast in our commitment to our ideals, we respect and accept that members of our Party can have deeply held and sometimes differing views. This diversity is a source of strength, not a sign of weakness, and so we welcome into our ranks those may hold differing positions. We commit to resolve our differences with civility, trust, and mutual respect, and to affirm the common goals and beliefs that unite us.

Image of Dred Scott that appeared in Century Magazine, 1887.

In an effort to preserve the balance of power in Congress between slave and free states, the Missouri Compromise was passed in 1820 admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. Furthermore, with the exception of Missouri, this law prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36° 30´ latitude line.

In 1854, the Missouri Compromise was repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

The Supreme Court decision Dred Scott v. Sandford was issued on March 6, 1857. Delivered by Chief Justice Roger Taney, this opinion declared that slaves were not citizens of the United States and could not sue in Federal courts. In addition, this decision declared that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional and that Congress did not have the authority to prohibit slavery in the territories.

The Dred Scott decision was overturned by the 13th Amendment (Ratified in December, 1865) and 14th Amendment (Ratified in July of 1868) to the Constitution.

Salmon P. Chase

Library of Congress

Salmon P. Chase[/caption]In 1854, Salmon P. Chase, Senator from Ohio, Charles Sumner, Senator from Massachusetts, J. R. Giddings and Edward Wade, Representatives from Ohio, Gerritt Smith, Representative from New York and Alexander De Witt, Representative from Massachusetts authored the “Appeal of the Independent Democrats” as a response to Senator Steven Douglas who introduced the “Kansas-Nebraska Act” in the same year. This act would superseded the Missouri Compromise and has been considered by some to be the “point of no return” on the nation’s path to civil war.

In fact, after the bill (Kansas-Nebraska Act) passed on May 30, 1854, violence erupted in Kansas between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, a prelude to the Civil War.

The act passed Congress, but it failed in its purposes. By the time Kansas was admitted to statehood in 1861 after an internal civil war, southern states had begun to secede from the Union.

The Independent Democrats and many northern Whigs abandoned their affiliations for the new antislavery Republican party, leaving southern Whigs without party links and creating an issue over which the already deeply divided Democrats would split even more.

Alvan Bovay

In Ripon, Wis., under the leadership of lawyer Alvan E. Bovay, representatives of various political groups took a strong stand against the Kansas-Nebraska Act and suggested the formation of a new party. Other anti-Nebraska meetings in Michigan, New York, and throughout the North that spring also recommended the organization of a new party to protest the bill.

In July of 1854, a convention was held in Madison to organize the new party. The members resolved, “That we accept this issue [freedom or slavery], forced upon us by the slave power, and in the defense of freedom will cooperate and be known as Republicans.” The Wisconsin Republican Party was dominated by former Whigs, yet they played down their backgrounds to concentrate solely on the issue of slavery, the one issue on which they knew all Republicans could agree.

When the 1854 election returns were in, Wisconsin Republicans had captured one of the two U.S. Senate seats, two of the three U.S. House of Representatives seats, a majority of the state assembly seats, and a large number of local offices. The next year, Wisconsin elected a Republican governor.

The first official Republican meeting took place on July 6th, 1854 in Jackson, Michigan.

Today in the town of Jackson, Michigan at the corner of Second & Franklin Streets, there is a historical marker that reads;

“Under the Oaks” Historical marker located in Jackson, Michigan.

“On July 6, 1854, a state convention of anti-slavery men was held in Jackson to found a new political party. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” had been published two years earlier, causing increased resentment against slavery, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of May, 1854, threatened to make slave states out of previously free territories. Since the convention day was hot and the huge crowd could not be accommodated in the hall, the meeting adjourned to an oak grove on “Morgan’s Forty” on the outskirts of town. Here a state-wide slate of candidates was selected and the Republican Party was born. Winning an overwhelming victory in the elections of 1854, the Republican party went on to dominate national parties throughout the nineteenth century.”

It is estimated that over 1,000 people attended this meeting, far exceeding the capacity of the hall event organizers had secured for the event. So as an alternative, the meeting was adjourned to an oak grove on “Morgan’s Forty” on the outskirts of town.

The name “Republican” was chosen because it alluded to equality and reminded individuals of Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party.

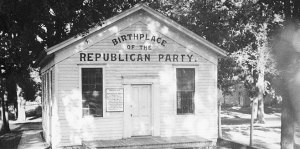

Birthplace of the Republican Party in Ripon, Wisconsin.

Was Wisconsin the birthplace of the Republican Party? Or was it in Michigan? Perhaps it was in Pennsylvania? That debate continues even to this day.

The name was first publicly applied to the movement in a June 1854 editorial by New York editor Horace Greeley, who said;

“It would fitly designate those who had united to restore the Union to its true mission of champion and promulgator of Liberty rather than propagandist of slavery.”

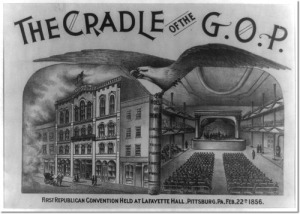

Local meetings were held throughout the North in 1854 and 1855. The first national convention of the new party was only held in Pittsburgh on February 22, 1856. Whether one accepts Wisconsin’s claim depends largely on what one means by the words “birthplace” and “party.” Modern reference books, while acknowledging the ambiguity, usually cite Ripon as the birthplace of the organized movement to form the party.

If not born in Ripon, the party was at least conceived there.

Lafayette Hall, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania

In January of 1856, a pro-Republican newspaper in Washington, D.C. published a call for representatives of the various state Republican organizations to meet in convention in Pittsburgh, PA with the dual purposes of establishing a national Republican organization and setting a date for a future nominating convention.

Representatives from northern states, as well as a number from several southern states and western territories, gathered in that city on Washington’s Birthday to set forth their common beliefs and political goals and to lay the groundwork for a national party. The Pittsburgh convention neither made nominations nor established a formal party platform; its representatives were not even formal delegates. Yet the Pittsburgh convention served as the first national gathering of the young Republican Party and successfully established the party as a legitimate national political institution while providing the Republicans with a sense of identity and unity.

This convention became the seminal event in the Republican Party’s formative years through its direct impact upon both the party’s early policies and the subsequent nominating convention in Philadelphia in June of that year.

The first organizational convention for the Republican Party was held in the Lafayette Hall (on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Wood Street) in downtown Pittsburgh.

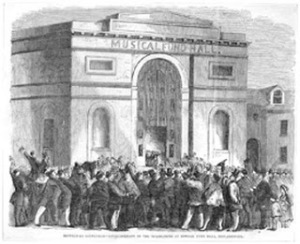

Musical Fund Hall, Philadelphia, Pa, site of first Republican National Convention.

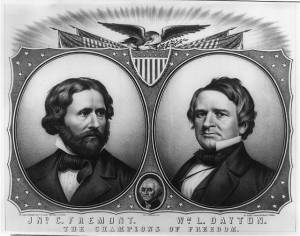

In 1856, the Republicans became a national party under the Republican Party Platform of 1856, nominating John C. Fremont of California for president. At the convention, Abraham Lincoln lost his bid as a vice presidential candidate to William L. Dayton, a former senator from New Jersey.

Fremont was a national hero who had won California from Mexico during the Mexican-American War and had crossed the Rocky Mountains five times.

Fremont, known more as an explorer than for his brief time as a U.S. senator, became the front runner after two major contenders withdrew from the race before the balloting began: Salmon P. Chase of Ohio and William H. Seward of New York. The 600 voting delegates at the convention represented the Northern states and the border slave states of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky and the District of Columbia. The symbolically important Territory of Kansas was treated as a full state.

First Republican candidate for President John Fremont and Vice Presidential Candidate William L. Dalton

The Republican platform advocated, like the Democrats’ platform, construction of a transcontinental railroad and welcomed improvements of river and harbor systems. The most compelling issue on the platform, however, was opposition to the expansion of slavery in the free territories and urgency for the admission of Kansas as a free state, calling upon “Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism — Polygamy and Slavery.”

The Republicans united under the campaign slogan;

“Free soil, free labor, free speech, free men, Fremont.”

John Fremont was defeated in the Presidential election of 1856 by Democrat by James Buchanan.

13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery

13th Amendment, which outlawed slaveryIn 1896, Republicans were the first major party to favor women’s suffrage. The Republican Party played a leading role in securing women the right to vote. When the 19th Amendment was finally added to the Constitution, 26 of the 36 state legislatures that had voted to ratify it were under Republican control.

The first woman elected to Congress was a Republican, Jeanette Rankin from Montana in 1917.

Jeannette Rankin’s life was filled with extraordinary achievements: she was the first woman elected to Congress, one of the few suffragists elected to Congress, and the only Member of Congress to vote against U.S. participation in both World War I and World War II.

“I may be the first woman member of Congress,” she observed upon her election in 1916. “But I won’t be the last.”

As the first woman Member, Rankin was on the front-lines of the national suffrage fight. During the fall of 1917 she advocated the creation of a Committee on Woman Suffrage, and when it was created she was appointed to it.

When the special committee reported out a constitutional amendment on woman suffrage in January 1918, Rankin opened the very first House Floor debate on this subject. “How shall we answer the challenge, gentlemen?” she asked. “How shall we explain to them the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country?”

The resolution narrowly passed the House amid the cheers of women in the galleries, but it died in the Senate.

The first woman to serve in both the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate was Margaret Chase Smith of Maine.

For more than three decades, Margaret Chase Smith served as a role model for women aspiring to national politics. As the first woman to win election to both the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate, Smith cultivated a career as an independent and courageous legislator. Senator Smith bravely denounced McCarthyism at a time when others feared speaking out would ruin their careers. Though she believed firmly that women had a political role to assume, Smith refused to make an issue of her gender in seeking higher office. “If we are to claim and win our rightful place in the sun on an equal basis with men,” she once noted, “then we must not insist upon those privileges and prerogatives identified in the past as exclusively feminine.“

On June 1, 1950, Margaret Chase Smith delivered in the Senate Chamber a “Declaration of Conscience” against McCarthyism, defending every American’s “right to criticize…right to hold unpopular beliefs…right to protest; the right of independent thought.” A Republican senator from Maine, Smith served 24 years in the U.S. Senate beginning in 1949, following more than four terms in the House of Representatives. She was the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress. At a time when it was unusual for women to serve in Congress, Smith chose not to limit herself to “women’s issues,” making her mark in foreign policy and military affairs. She established a reputation as a tough legislator on the Senate Armed Services Committee. She also became the first woman to run for president on a major party ticket in 1964. When she left the Senate in 1973, Smith retired to her home in Skowhegan, Maine, where she died in 1995, at the age of 97.

Born on March 26, 1930, in El Paso, Texas, Sandra Day O’Connor went on to become the first female justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1981. Long before she would weigh in on some of the nation’s most pressing cases, she spent part of her childhood on her family’s Arizona ranch. O’Connor was adept at riding and assisted with some of ranch duties. She later wrote about her rough and tumble childhood in her memoir, Lazy B: Growing Up a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest, published in 2003.

In 1973 while serving in the Arizona State Senate, Sandra Day O’Connor was chosen by her fellow Senators to become the first female majority leader of any state senate in the United States.

In 1974, she took on a different challenge. O’Connor ran for the position of judge in the Maricopa County Superior Court. As a judge, Sandra Day O’Connor developed a solid reputation for being firm, but just. Outside of the courtroom, she remained involved in Republican politics. In 1979, O’Connor was selected to serve on the state’s court of appeals.

On September 25th, 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was sworn into office as a Justice of the United States Supreme Court, nominated to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan.

O’Connor blazed a trail into the highest court in the land, winning unanimous support from the Senate as well as then-United States Attorney General William French Smith.

After Judge O’Connor’s appointment, she served from 1981 until 2006 and was the valued “swing” vote on many important legal and social issues that came before the court at that time.

As Republicans, we believe;

Many thanks to the Republican Party of Virginia Beach for sharing content from their website