by Christian Braunlich, December 16th, 2024 at ThomasJeffersoninst.org

More than 70 years ago, black and white students in Virginia received separate and very unequal educations.

In They Closed Their Schools, author Bob Smith writes that in Farmville, a city not unlike the rest of Virginia, the white public school built after a 1939 fire “had a gymnasium, cafeteria, locker rooms, infirmary and an auditorium with fixed seats.” Moton High School, built for black students in 1939, had none of these. Constructed to accommodate 180 students, by 1950 it held 470 – so many that the school held three classes in the auditorium (“one on stage, two in the back”), and occasionally a class on the school bus. The white schools were having none of that.

Those buses had been discarded by the white schools, as were the textbooks, as were other supplies. Teachers were paid about 40 percent less than white counterparts. And the curriculum for black students emphasized vocational training, especially agriculture … which coincidentally allowed courses to be taught outdoors and relieve the overcrowding that forced students to be taught in “tarpaper shacks”.

That dual system muddled along for nearly four decades until, in 1951, 16-year-old Barbara Johns shined a spotlight on it when she led students in a walk-out to demand equal education. She faced opposition not only from a white education establishment but also from an older generation of black leaders worn down by time. Her own attorneys, notably Oliver Hill, questioned the effort but ultimately the light she shone resulted in her cause becoming part of Brown v. Board of Education.

Over time (too much time), educational inputs narrowed significantly. But educational outcomes remained lower than desired and achievement gaps remained large.

To address the issue, President George W. Bush and Senator Ted Kennedy united to pass the No Child Left Behind law (NCLB), a hallmark of which required states to uniformly measure student progress, particularly among disadvantaged students, through use of standardized tests.

Each state was to develop its own exams and standards, but to confirm state progress by benchmarking against the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), considered the gold standard by educators throughout the country.

Virginia, first in the nation to have its own standards, exams, and training for educators was already ahead of the game. By the time NCLB rolled around three years after the SOL program begun by Governor George Allen, the Commonwealth had already invested nearly $42 million ($76 million in 2024 dollars) in teacher training alone.

NAEP’s random sampling provided disaggregated scores so the public would understand how well different student demographics performed. The scores of Black, White, Hispanic, Asian, Low-income, special needs, and English Learners would be transparent. No longer could school districts utilize the outstanding achievements of middle-class students to hide failures at the bottom.

Unable to tolerate the light of transparency, however, the National Education Association teachers’ union sued to overturn NCLB. The courts dismissed the lawsuit as did The New York Times noting “The NEA has misrepresented the law to the public from the start.”

Alas, the union eventually won in Congress, when the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) abandoned NCLB and its focus on helping the educationally at-risk succeed. The result was that student achievement gaps, which had narrowed over the previous decade but no longer had bright light shining on them, began to grow.

It was especially egregious in Virginia, made more apparent by Covid. This was, after all, a system that by now had “made it much easier for schools to win state accreditation,” fostered by a Governor who once suggested that poor children might be given a different test.

As a result, in August the Glen Youngkin-appointed Board of Education approved a new school performance and support network, to strengthen Virginia’s accountability and eliminate deficiencies hurting students while making adults look good.

Writing in the blog Bacon’s Rebellion, Arlington parent Todd Truitt, a self-described “Obama Democrat,” forcefully described the advantages of the new system and how it better supports advanced math learners, follows long-standing federal policy for English Learners, and even why Democrats should support the new accountability system.

Yet, the largest patron of Democratic candidates for office – the Virginia Education Association union – is massively resisting. The VEA website argues that, because a high percentage of students in “Needs Intensive Support” schools are black or English Learner students, the framework is inherently unfair because teacher vacancy rates at those schools are higher and teacher positions unfilled.

Of course, one solution would be to offer higher salaries to better teachers to teach in those schools. This is a solution unacceptable to the union, which demands all teachers (regardless of capability or subject) receive bigger salaries (from which, by the way, it might extract higher levels of union dues.)

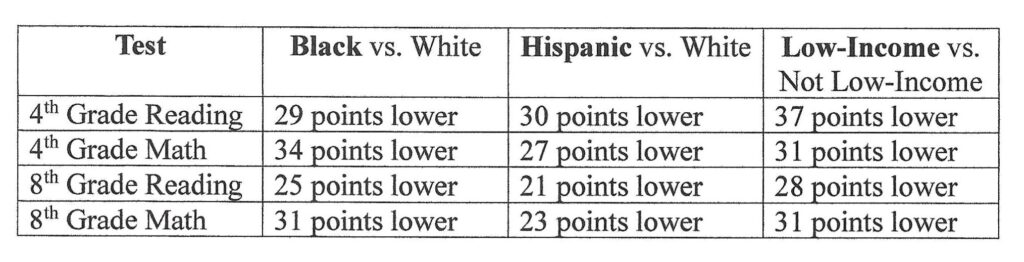

Nor is the framework exposing anything not already known, even if previously invisible to ordinary Virginians. In the latest administration of NAEP, the gaps involving ethnicities and income are significant:

Among others, Black, Hispanic, and Low-Income students do not fare as well … but their parents have to dig for the details on a federal website to find out. Instead, they are frequently told “Nothing to see here,” even as their children enter the playing field of life unprepared.

That makes accountability even harder in a state like Virginia, where school boards have “manifest power” to run their schools. There is no “higher authority” to force changes in curriculum, personnel, or budget. Accountability relies almost exclusively on the highest authority – the voters. But for that to work — for parents to be genuinely involved in their child’s education — parents must understand where their children stand, in simple declarative language.

Does the VEA seriously suggest that revealing deficiencies in the educational outcomes of some Virginia students is wrong? Or is it simply easier to turn out the lights rather than expose adult failure?

Indeed, the precise point of such exposure is to demonstrate which schools and students struggle, so parents can demand action, and to direct the right resources to those schools and students.

Providing additional resources is precisely what Governor Youngkin has started. Understandably, given its previously displayed animosity to the Governor, that makes it hard for the VEA to applaud doing the right thing … just as burying disaggregated scores makes it harder for parents to demand improvements to their local school.

Seventy-three years ago, the world changed because a 16-year-old high school student shined a light on inequity. Exposing the inequities of today will take a bigger and brighter light, but the alternative is to remain in the dark.