By Asra Q. Nomani and Sravan Gannavarapu – December 9th, 2024

Ruby Garnet Beckwith, a Fairfax County mother, and U.S. Marine Corps veteran, spent nearly a decade nurturing her son’s love for football. Ever since he was 5 years old, she had driven him to practices, games, and camps, ensuring he had every opportunity to pursue his dreams. When he made the Hayfield Hawks football team as a freshman last year, it felt like all the hard work had paid off.

But what started as a moment of pride for Beckwith’s family soon turned into a nightmare with the arrival of a new football coach and the launch of a new campaign to put Hayfield Hawks football on the map at any cost. Nine months later, the school’s Athletic Director, Monty Fritts, is out of a job after the Fairfax County Times revealed a series of text messages that implicated him in an alleged scheme exploiting federal laws for homeless students to quickly transfer football players from neighboring Freedom High School in Prince William County to Hayfield, leaving existing players like Beckwith’s son in the dust. Fritts left behind irate parents and dispirited students, a shattered school reputation, a football team in shambles, and questions if he is just a scapegoat for accountability that needs to go higher up the chain of command.

Hayfield’s parents wonder why it took months to oust Fritts, given the number of whistleblowers, the paper trail of tips and complaints, and the players’ dropping morale.

A series of emails, whistleblower reports, and other documents obtained by the Fairfax County Times reveal that starting in February, top FCPS and Hayfield officials, including FCPS Superintendent Michelle Reid, Assistant Superintendent Michelle Boyd, Principal Darin Thompson, and Head Coach Darryl Overton, received at least 35 warnings over nine months from at least 19 whistleblowers – three moms, one dad, seven FCPS staffers, and eight FCPS football coaches – dismissing the warnings of shady dealings at every turn until the revelations of the text messages by Fritts forced Reid and Thompson to withdraw Hayfield from the state playoffs last week. Complaints about favoritism, bullying, and the exploitation of transfer rules went unaddressed, eroding trust in the administration. FCPS officials have denied wrongdoing.

Three board members—Mateo Dunne, Ryan McElveen, and Ricardy Anderson—plan to demand an independent, external investigation at a school board meeting Thursday night. Angry parents plan to flood the meeting, alleging a coverup. Thompson told Virginia High School League investigators “that he was not aware of unusual transfer activity from Freedom until June.”

FCPS spokeswoman Julie Allen said: “Complaints and concerns from our students, staff, and parents are taken seriously. The Superintendent’s Office and FCPS senior leadership refer all complaints and concerns they receive to the appropriate school division staff for review and resolution. We are not able to share confidential information about student matters due to federal and state laws.”

It all began with a happy announcement. On Feb. 13, Thompson and Fritts introduced the new coach, Overton, to much fanfare. Overton, a two-time state champion at Freedom High School in neighboring Prince William County, was hailed as the coach who would transform the Hayfield program. Parents were optimistic, and students were eager to learn from someone with such a celebrated track record.

Beckwith’s son was no exception. However, within days, it became clear to returning players that Overton’s focus was not on the existing players, sources said. A wave of new athletes—transfers from Freedom —began appearing at practices, dominating the weight room and monopolizing the coach’s attention.

One night, Beckwith’s son confided in her, “Mom, I’m working hard, but it feels like I don’t matter.”

February: U.S. Marine Corps veteran and mom rings alarm about transfers in 23-minute call with coach

Beckwith noticed the shift almost immediately. Her son, who had always been enthusiastic about football, came home dispirited. “It was obvious that the Freedom players were being prioritized,” Beckwith recalled.

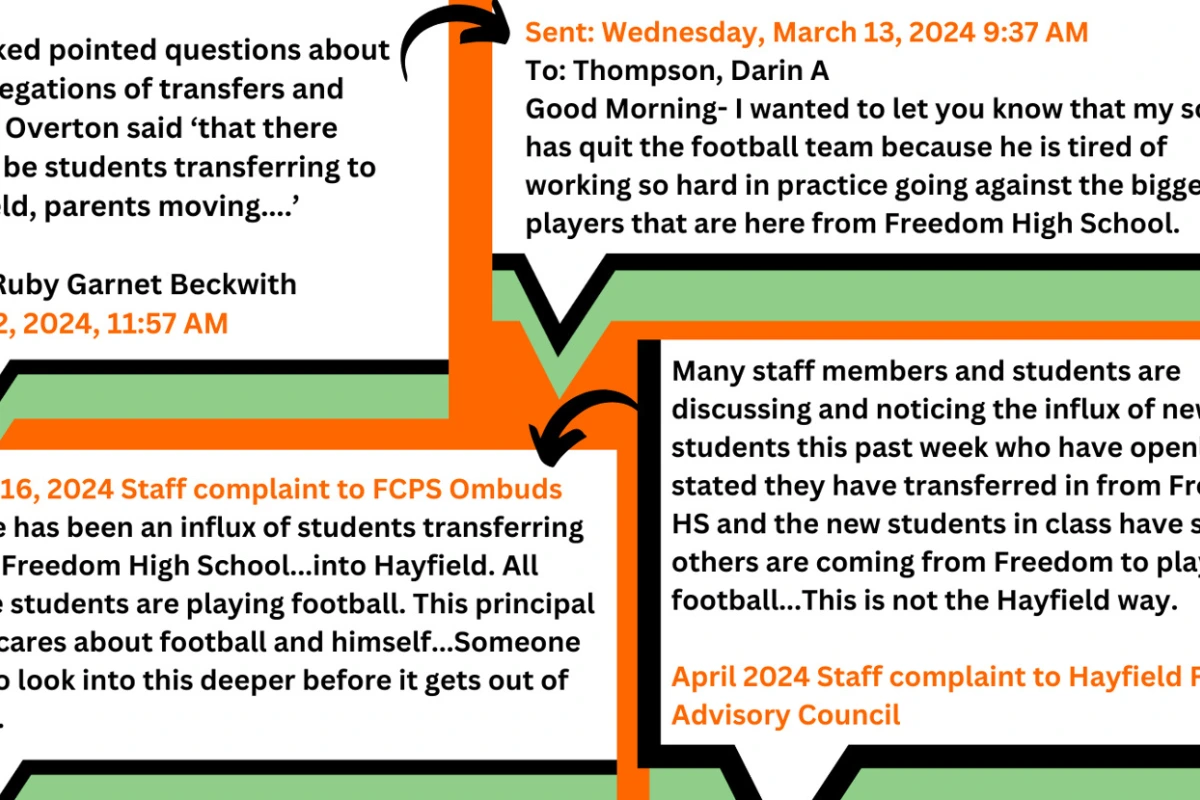

On Feb. 22, nine days after Overton started, Beckwith and her husband called the coach to address their concerns. The 23-minute call began at 11:57 a.m. and was pointed but polite. They asked Overton directly about the influx of new athletes.

Overton didn’t deny it. “They’re moving here to follow me,” he said. He framed the transfers as a sign of his coaching reputation, arguing that parents were making sacrifices to give their children the best opportunities.

Beckwith found the explanation troubling. “I don’t have a problem with parents making sacrifices for their kids,” she said later. “But not when it’s done at the expense of other children’s futures or by breaking the rules.”

Her son’s morale continued declining, as did his fellow players.

Around this time, Regina Dorsey, a career U.S. Army soldier and mom whose son was on the team, asked the athletic director about rumors of illegal transfers. He assured her “there wasnothing illegal going on with the new Coaching staff ( recruiting and money issues),” which she later shared with the principal in May.

March: Mom warns principal transfers ‘pushing the Hayfield STUDENT players out’

After just one month into Overton’s start at Hayfield, a second mother raised a red flag with Thompson about improper transfers on the football team. She informed him that her freshman son had quit the team because the transfers were “pushing the Hayfield STUDENT players out.” She had seen several football players pile out of a vehicle at the 7-11 on Telegraph Road and walked over to Hayfield.

On March 13 at 9:37 a.m., the mother of three fired off an email to Thompson, writing, “I wanted to let you know that my son has quit the football team because he is tired of working so hard in practice going against the bigger players that are here from Freedom High School. He knows that even though he was a starter last fall on the freshman team he is not going to get much play time because of these better players that are here from Freedom. They are pushing the Hayfield STUDENT players out.”

“How is it possible that these players coming from Freedom are going to play for Hayfield when they don’t live in the district?” the mother asked.

The principal didn’t respond. Instead, at 8:07 p.m. that evening, Fritts replied with a carefully crafted message, “I met with our new Head Coach about this today. I assure you only players that attend Hayfield will be playing Football at Hayfield.”

Fritts signed off, “GO HAWKS!!!”

But the response sidestepped the real issue: Were the transfers legitimate?

The mom wasn’t satisfied, but there was little she could do. The following day, at 8:28 a.m., she replied, saying her son had lost his love for the sport. “He said he has lost the fun in football for right now.”

Early April: Faculty member tells FCPS ombudsman transfers arriving to ‘pad the football team’

By April, Hayfield staff had compiled a list of 16 “out of county” transfers joining the football team. Two Hayfield staffers filed complaints in an anonymous portal reviewed by the principal and the school’s faculty advisory council. In the first complaint, a staffer wrote: “Many staff members and students are discussing and noticing the influx of new students this past week who have openly stated they have transferred in from Freedom HS and the new students in class have stated others are coming from Freedom to play football. I don’t know the ins and outs of rules but this can throw a negative light on Hayfield as it gives the impression that recruiting is openly taking place. This is not the Hayfield way.”

A second complaint noted: “If recruiting is allowed for football because the…new coach is from Freedom, then why can’t all other sports openly recruit as well? This does not leave a good taste in Hayfield’s perception.”

On April 16, at 5:24 p.m., a faculty member filed a complaint, raising alarms about the transfers with the FCPS Office of the Ombuds, which reports to FCPS Chief Experience and Engagement Officer Lisa Youngblood Hall, a member of Reid’s leadership team and a hand-selected pick from Reid’s previous job in Washington state.

“There has been an influx of students transferring from Freedom High School (Prince William County) into Hayfield,” the complaint read, asking questions about the new football players. “All these students are playing football. How do they know if they have made the team. VHSL has strict restrictions for recruitment and I am saddened that the principal is allowing all these transfers into the building to pad the football team. Today, he made the Head Football Coach (who is his friend) the Security Specialist.”

The complaint criticized Thompson’s priorities. “The principal only cares about football and himself,” the faculty member wrote. “The culture of the school is exasperating and very dysfunctional.”

“Someone has to look into this deeper before it gets out of hand,” the complainant pleaded, asking, “How do we identify the rules and regulations to protect the integrity of the school?”

The following day, at 9:07 a.m., an Office of the Ombuds administrative assistant responded with a stock reply to schedule a meeting to discuss “your questions and concerns.”

Late April: Longtime administrator warns FCPS that football controversy is “really getting bad”

Around April 23, a trusted longtime FCPS administrator emerged, raising red flags. Dale Eaton, a retired FCPS assistant principal and football coach, had worked at Hayfield the year before as an interim assistant principal, and he knew the school community well. Around April 19, he texted a longtime colleague, Bill Curran, director of the FCPS Office of Student Activities and Athletics, which oversees sports teams, a warning about the football team.

Eaton wrote to Curran, “The optics on this situation is really getting bad and some people are going to be in trouble.”

At a May 1 track meet, even the track and field team’s coaches were left shaking their heads when the athletic director added 10 football players to their roster without practicing with the team.

“They were not there to be track athletes,” said someone familiar with the meet.

Thompson notified the VHSL in September that seven of the track athletes were ineligible to compete.

Meanwhile, Eaton spoke to Hayfield’s director of student services, Erin Crowley, a Hayfield graduate he had long known from working with her mother, and warned her that something seemed awry with the transfers. According to sources, Crowley raised the question with Thompson.

Mid-May: U.S. Marine veteran mom says football coach ‘humiliated’ her son for fake ‘hate crime’

Two weeks later, Beckwith’s high schooler faced a different challenge. On May 13, an administrator accused him of writing offensive words in chalk outside the school in an alleged “hate crime.” Beckwith watched the security footage, which showed her younger son had written the words in an act of middle school indiscretion.

Despite this, she learned that Overton had punished her older son, making him and a friend pick up trash around the school in front of his teammates. “They were humiliated in front of everyone,” Beckwith said. “The punishment wasn’t just unfair—it was targeted.”

In another corner of the school, Eaton went by Hayfield on May 14 when Thompson took him aside. According to a letter Eaton sent Reid and Boyd, the assistant superintendent, Eaton wrote, “He seemed very concerned about the issue of his football program and his coach.”

Late May: U.S. Army mom files complaint with VHSL and FCPS about ‘fake address scheme’

By late May, Dorsey, the U.S. Army mom, had even more questions about the new changes than when Overton started three months earlier. She’d already asked about a new $200 “player’s fee” that could be paid through CashApp.

On May 20, Dorsey spoke to another Hayfield mother, an active-duty military member, and asked her point blank “if she was tied into this fake address scheme with Hayfield Football.” The friend told her that “she was doing a favor” but agreed to back out.

The next day, May 21, Dorsey filed a complaint with Ty Gafford, the assistant director of compliance at the Virginia High School League.

That day, her son told her he had been booted from a group text with other football players. When he asked questions, he was asked if he saw a message about another group chat. Her son replied: “Naw all I see is you kicked me n only me 💀,” punctuating his reply with a skull emoji.

Three days later, on May 24, Thompson responded with the results of his investigation: the bullying “allegation was determined to be unfounded” against Dorsey’s son. His removal from the team text “was coincidental.” Thompson wrote that the trust quote “was made to successful secondary coverage hinging upon trusting each other.”

On May 28, Dorsey sent an email at 4:25 p.m. to Thompson, copying Gafford, VHSL’s assistant director of compliance. It was clear to her what had happened: Overton and his staff were exacting “a form of revenge” upon her son for her raising concerns. “I felt like it was retaliation for me making the report with my concerns,” she wrote.

Two days later, Dorsey wrote to Curran and Tom Horn, the top two officials in FCPS’s Office of Student Activities and Athletics, reporting to FCPS Chief of Schools Geovanny Ponce, who reports to the superintendent.

June: A boy quits the football team and public outcry

Across town, on June 1, Beckwith, the Marine veteran mom, sat at her kitchen table when her son walked in, his face drawn with sadness.

“I’m not going to play football anymore,” he said.

The next week, on June 11, Thompson broke some shocking news to the staff: he was transferring the student services director Crowley to Annandale High School in a job swap with Erik Healey, the director of student services at Annandale. Crowley cried softly, according to people familiar with the situation. Not long ago, Healey was promoted to principal at Centreville High School.

On June 22, the Fairfax County Times published its first article on allegations of recruiting violations at Hayfield. Beckwith was surprised by what she read, not in the article, but in the comment board: a chronicling of the “hate crime” charge wrongly leveled against her freshman son.

The following week, on June 24, a new whistleblower emerged: Greg Keeney, a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel with 30 years in military intelligence. His son had left the team.

The week after, in late June, another Hayfield staffer filed a concern with the school district’s ombudsman, Dawn Clements, about the “toxic culture” at Hayfield Secondary School and Thompson’s “autocratic style of leadership” as a “dictator.” The staffer sent a copy of the concerns to Reid.

The staffer never heard back.

September: A Mother’s Last Stand

By September, Beckwith had reached her breaking point. On September 12, she addressed the school board in a public meeting, delivering an emotional two-minute speech. Days later, the coach’s brother, Jeff Overton Sr., a security official at the school and an assistant coach, followed her youngest son back to his classroom after he took a restroom break and demanded he wash a dirty dish. The classroom had a sink.

“It wasn’t just inappropriate—it was demeaning,” Beckwith said. “No adult should be treating a student that way.”

Beckwith saw the cumulative impact of these incidents on her children. Her older son “went from being a confident, hard working athlete to questioning his self-worth.” This week, she pulled her youngest son from Hayfield.

“This isn’t just about football—this is about the culture at Hayfield,” Beckwith said. “The administration failed to protect students, foster fair play, and uphold basic ethical standards.”

“This isn’t just about my sons,” she added. “It’s about every kid who’s been overlooked, mistreated, or made to feel less than they are.”